SPRING PNWAS

Thursday, May 9th, 2024

(starting at 5:30 pm since Dr. Lin on East Coast ET!!)

Thursday, May 9th, 2024

(starting at 5:30 pm since Dr. Lin on East Coast ET!!)

The History of "Woolly Dogs" revealed

by Ancient Genomics and Indigenous

Knowledge

By Audrey T. Lin, U.S. Smithsonian,

Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa, Vancouver Island University

and many others...

by Ancient Genomics and Indigenous

Knowledge

By Audrey T. Lin, U.S. Smithsonian,

Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa, Vancouver Island University

and many others...

PNWAS ZOOM Meeting

Thursday February 29th 2024

starting at 5:30 PM

To join the ZOOM Meeting and see the presentation

please become a member today!

Thursday February 29th 2024

starting at 5:30 PM

To join the ZOOM Meeting and see the presentation

please become a member today!

Woolly Dogs were recorded from earliest contact on the Northwest Coast:

- 1792: Captain George Vancouver—Port Orchard: dogs “shorn as close to the skin as sheep are in England…with very fine long hair”

- 1792: Joseph Whidbey observed native people “walking along the shore” of Camano Island “attended by about 40 dogs in a drove, shorn close to the skin like sheep.”

- 1792: Spanish: Gabriola Island: “the great number of dogs they keep in their villages, most of which were shorn” “of moderate size, resembling those of the English breed, very woolly, and usually white.”

- 1806: Simon Fraser observed shorn dogs and blankets made from goat and dog hair.

- 1824: seamen of the William and Ann observed that the Makah kept their woolly-dogs isolated “on a little island a few miles from the coast” where they feed them every day.

- 1826: James McMillan observed a flotilla of 160 Cowichan canoes on the Fraser River returning from fall salmon fishing upstream, each canoe with “about half a dozen dogs more resembling Cheviot Lambs shorn of their wool” (over ~900!).

- 1847: Paul Kane described woolly-dogs with long black, brown, or white hair that was sheared with a knife, Lower Elwha Klallam (see his painting below).

- 1858: and MUTTON >>>>

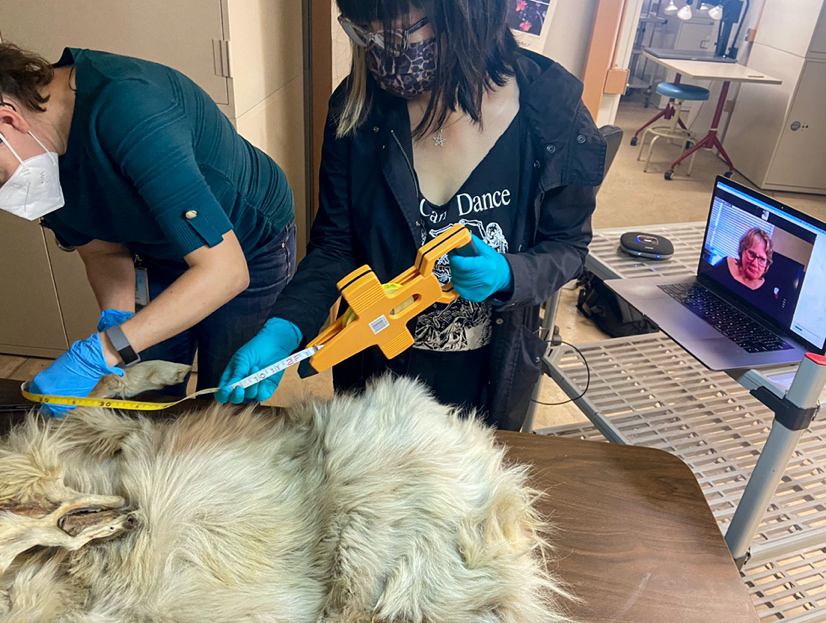

Woolly dog Mutton’s pelt spent more than 160 years housed in

the Smithsonian when Dr. Audrey Lin re-located him where

she worked. In 1858, Mutton was adopted by George Gibbs, a

naturalist and ethnologist working in the Northwest. As a scientist Gibbs believed Mutton was a distinct Indian dog, and after his death, he sent his pelt and lower leg bones, to the

Smithsonian collections. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian

National Museum of Natural History.

The story of woolly dogs, such as Mutton, is well presented by Virginia Morell in Hakai Magazine, 2- 23-21 (link below):

There was a time when the Indigenous women of the Pacific Northwest’s coastal regions paddled their canoes to small, rocky islands once a day or so to care for packs of small, white-furred dogs. The dogs would greet them, yelping and pawing as they implored their keepers for food. The women, in turn, would pet the dogs and dispense a stew of fish and marine mammal bits—not scraps, but quality food. Once the dogs (most of them perhaps females, probably in heat) had eaten their fill, the women might linger awhile to sing to them and brush their long white fur.

The dogs—and their fur—were the women’s source of wealth, and the women kept watch to ensure that no village cur crept onto the islands to taint the breed. Once or twice a year, the women arrived as usual with a supply of food, but also brought mussel-shell knives. The dogs knew the routine: settle down and relax so that the women could cut away their white tresses, shearing the dogs as closely as shearers do sheep.

Back in their village longhouses, the women transformed that fur into yarn, spinning it and mixing it with the wool of mountain goats and adding plant fibers and goose down to make the thread strong and warm. They beat the yarn with white diatomaceous earth to deter insects and mildew. They dyed some of the yarn red with alder bark, tinted it a light yellow with lichen, and produced blue and black threads using minerals or huckleberries. The rest—an ivory-hued yarn—they set aside. Then the women set up their looms and began to weave, turning out twill-patterned blankets of various sizes, some with elaborate and colorful geometric designs, others with simple stripes. The dogs did more than provide fur. They were also part of village life: sometimes, a favorite wooly dog would keep a weaver company (Morell 2021:1).

Comparing Mutton’s DNA to that of hundreds of other dog breeds, Dr. Lin found that he was indeed a woolly dog. Or, rather, Mutton was about 84 percent woolly dog, and shared about 16 percent of his ancestry with European breeds, such as English cocker spaniel and Dalmatian.

Dr. Iain McKechnie, co-author and archaeologist at the University of Victoria and the Hakai Institute, says Mutton’s genome may be the key that unlocks the genetic history of woolly dogs and the various subtypes that occur in the archaeological record.

There was a time when the Indigenous women of the Pacific Northwest’s coastal regions paddled their canoes to small, rocky islands once a day or so to care for packs of small, white-furred dogs. The dogs would greet them, yelping and pawing as they implored their keepers for food. The women, in turn, would pet the dogs and dispense a stew of fish and marine mammal bits—not scraps, but quality food. Once the dogs (most of them perhaps females, probably in heat) had eaten their fill, the women might linger awhile to sing to them and brush their long white fur.

The dogs—and their fur—were the women’s source of wealth, and the women kept watch to ensure that no village cur crept onto the islands to taint the breed. Once or twice a year, the women arrived as usual with a supply of food, but also brought mussel-shell knives. The dogs knew the routine: settle down and relax so that the women could cut away their white tresses, shearing the dogs as closely as shearers do sheep.

Back in their village longhouses, the women transformed that fur into yarn, spinning it and mixing it with the wool of mountain goats and adding plant fibers and goose down to make the thread strong and warm. They beat the yarn with white diatomaceous earth to deter insects and mildew. They dyed some of the yarn red with alder bark, tinted it a light yellow with lichen, and produced blue and black threads using minerals or huckleberries. The rest—an ivory-hued yarn—they set aside. Then the women set up their looms and began to weave, turning out twill-patterned blankets of various sizes, some with elaborate and colorful geometric designs, others with simple stripes. The dogs did more than provide fur. They were also part of village life: sometimes, a favorite wooly dog would keep a weaver company (Morell 2021:1).

Comparing Mutton’s DNA to that of hundreds of other dog breeds, Dr. Lin found that he was indeed a woolly dog. Or, rather, Mutton was about 84 percent woolly dog, and shared about 16 percent of his ancestry with European breeds, such as English cocker spaniel and Dalmatian.

Dr. Iain McKechnie, co-author and archaeologist at the University of Victoria and the Hakai Institute, says Mutton’s genome may be the key that unlocks the genetic history of woolly dogs and the various subtypes that occur in the archaeological record.

Hear the amazing story of unravelling the mystery of the domestication of Northwest Coast woolly dogs for their hair quality for making the wealth, blankets, on true looms in the Salish Sea. A biologist, Dr. Audrey Lin (DNA specialist), anthropologist, Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa, an archaeologist Dr. Ian McKechnie and Indigenous weavers will present their epic collaboration to unveil the life story of ancient woolly dogs found only in the Salish Sea region. All beginning with the examination of Mutton:

You may have seen this in Science magazine and two Hakai Magazine articles (at end of first article click on updated article on new discoveries):

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adi6549?fbclid=IwAR2HSbWhupeMnx0-ZPiChffcwbh4MzgbyDbksa6JcAm62nlHGI0TWvuDlhg

and:

https://hakaimagazine.com/features/the-dogs-that-grew-wool-and-the-people-who-love-them/

and https://hakaimagazine.com/news/the-story-of-the-indigenous-wool-dog-told-through-oral-histories-and-dna/

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adi6549?fbclid=IwAR2HSbWhupeMnx0-ZPiChffcwbh4MzgbyDbksa6JcAm62nlHGI0TWvuDlhg

and:

https://hakaimagazine.com/features/the-dogs-that-grew-wool-and-the-people-who-love-them/

and https://hakaimagazine.com/news/the-story-of-the-indigenous-wool-dog-told-through-oral-histories-and-dna/