LATE WINTER

PNWAS ZOOM Meeting

Thursday February 9th, 2023

PNWAS ZOOM Meeting

Thursday February 9th, 2023

A Quarter of a Million Salal Berries and Potential for

2.5 Million Acorns from Central Northwest Coast Archaeological Wet Sites--

Time to Recognize their Past Plant Food Significance

By Dale R. Croes, WSU and PNWAS

2.5 Million Acorns from Central Northwest Coast Archaeological Wet Sites--

Time to Recognize their Past Plant Food Significance

By Dale R. Croes, WSU and PNWAS

PNWAS ZOOM Meeting

Thursday December 15th 2022

starting at 6:30 with program at 7:00 PM

To join the ZOOM Meeting and see the presentation

please become a member today!

Thursday December 15th 2022

starting at 6:30 with program at 7:00 PM

To join the ZOOM Meeting and see the presentation

please become a member today!

Three Central Northwest Coast wet sites have begun to highlight the significance of berries and nuts, particularly salal and acorns, to ancient subsistence practices. At the Ozette site, mudslide encased houses and middens dating to 300–450 years ago produced flotation samples of 250,000 seeds of Salal. At the Sunken Village site, located on Sauvie Island, Oregon, over 100 hemlock-lined acorn leaching pits dated to 150–700 years ago have been recorded. It is estimated that these leaching pits may represent processing of 2,500,000 acorns in a season. Finally, at the QwuɁgwǝs site, located on South Puget Sound, Washington, reanalysis of macrobotanical artifacts

lead to the discovery that acorns were also abundant in the site midden. Acorn remains were seven times more common than hazelnut remains here, indicating that acorns might have been the most ubiquitous plant food at this south Salish Sea site.

lead to the discovery that acorns were also abundant in the site midden. Acorn remains were seven times more common than hazelnut remains here, indicating that acorns might have been the most ubiquitous plant food at this south Salish Sea site.

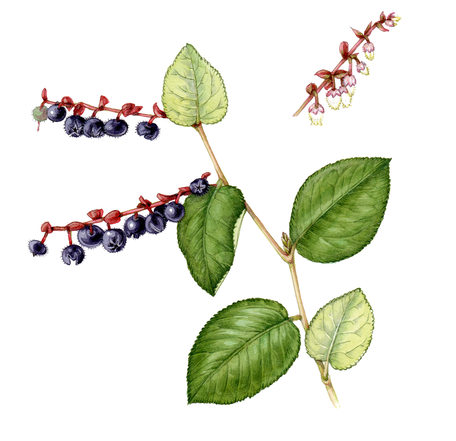

Northwest Coast archaeological wet sites, preserving wood and fiber materials, have begun revealing new insights on the use of plant foods by ancestral peoples not well recognized in the recent anthropological literature. I will discuss two main “crops” that reflect these archaeological acumens, salal berries (Gaultheria shallon, above top) and acorns (Quercus garryana, above bottom).

Salal berries (Gaultheria shallon).

Though not a Euro-american preferred food, it’s importance for Northwest Coast indigenous diets is often reflected in the literature. In Turner’s recent two-volume set, she records 32 languages that record names for salal, including 17 Salish and 7 Wakashan language families. As a berry widely eaten by Coastal peoples, she points:

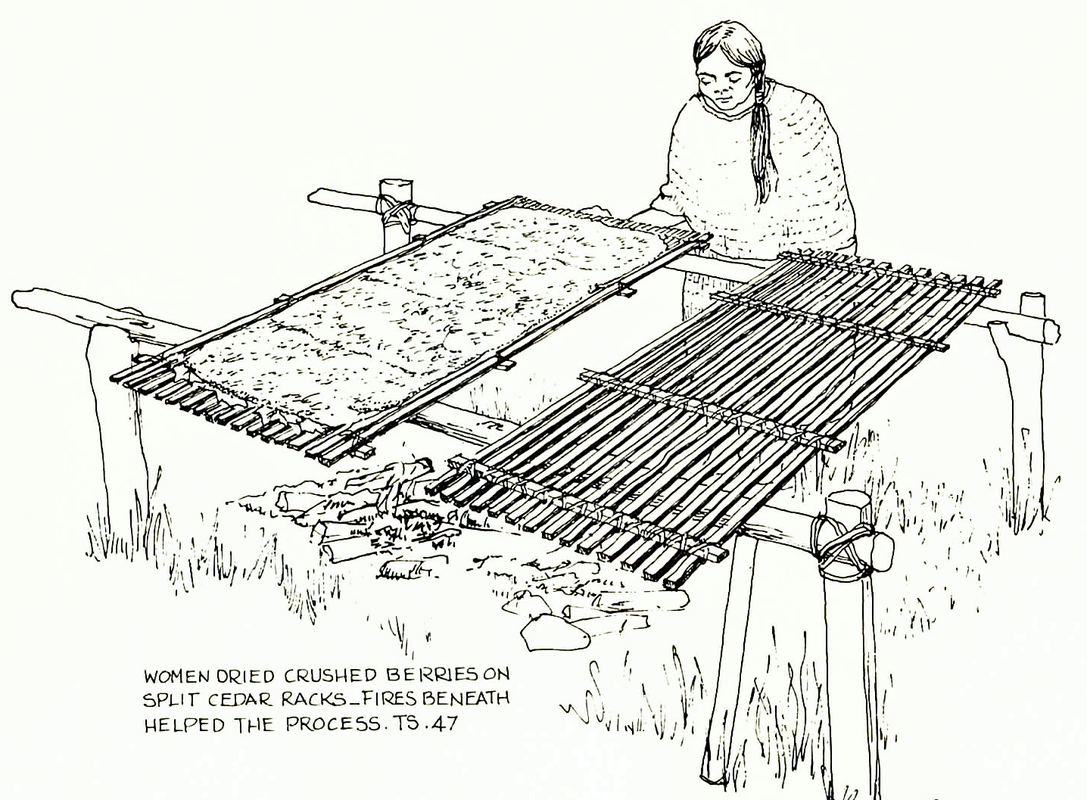

"Salal berries are without doubt the most plentiful and widely used fruit on the coast…They picked them in clusters in late summer and ate them fresh or dried them in cakes for winter. The Kwakwaka’wakw ate the

ripe berries at large feasts; they dipped the berry clusters in Grease and ate the berries one at a time, they threw the stems in the fire."

"Salal berries are without doubt the most plentiful and widely used fruit on the coast…They picked them in clusters in late summer and ate them fresh or dried them in cakes for winter. The Kwakwaka’wakw ate the

ripe berries at large feasts; they dipped the berry clusters in Grease and ate the berries one at a time, they threw the stems in the fire."

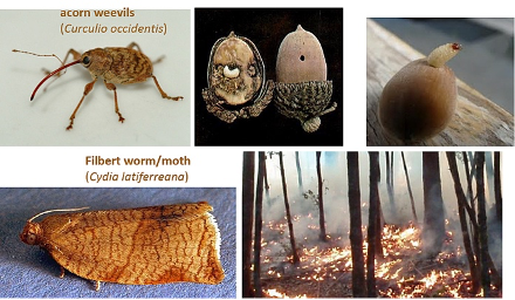

Quercus Garryana Oregon White Oak acorns.

Erna Gunther recognized acorn as a food in her Ethnobotany of Western Washington (1945) as follows:

"The oak occurs in this area only where there is open prairie country.

Chehalis: sk’wi’sl; skEkslalox, little

oak; kiloi, little leaves

Cowlitz: ts’ u’nips

Klallam: q!aput

Squaxin: tca’dzats

Food. The Nisqually, Chehalis, Cowlitz, and Squaxin, who live in sections where oak trees are most numerous,

use the acorn as food, but in the true evergreen forest area that is an unknown dish. The Chehalis roast acorns

in the fire. Acorns are stored in baskets of young maple bark and buried in mud of a slough all winter. In the

spring when they are taken out to eat, they look as though they were spoilt, but they are delicious. The Cowlitz bury acorns in the mud to leach them. The Squaxin roast them on hot rocks. The Klallam eat the acorn as a nut without preparation. The Quinault never use them as food. Since they are eaten in such small quantities the amount of tannic acid in them is not dangerous, and the elaborate leaching process used in northwest California, where the acorn is a basic food, is not necessary."

Our recently excavated over 100 acorn leaching pits from the Sunken Village wet archaeological site, Sauvie Island, Portland, Oregon is the largest acorn pit leaching archaeological site anywhere along the entire West Coast of North America (including Oregon/California), this wet site certainly reflects the importance of this food

on the Central Northwest Coast of North America.

"The oak occurs in this area only where there is open prairie country.

Chehalis: sk’wi’sl; skEkslalox, little

oak; kiloi, little leaves

Cowlitz: ts’ u’nips

Klallam: q!aput

Squaxin: tca’dzats

Food. The Nisqually, Chehalis, Cowlitz, and Squaxin, who live in sections where oak trees are most numerous,

use the acorn as food, but in the true evergreen forest area that is an unknown dish. The Chehalis roast acorns

in the fire. Acorns are stored in baskets of young maple bark and buried in mud of a slough all winter. In the

spring when they are taken out to eat, they look as though they were spoilt, but they are delicious. The Cowlitz bury acorns in the mud to leach them. The Squaxin roast them on hot rocks. The Klallam eat the acorn as a nut without preparation. The Quinault never use them as food. Since they are eaten in such small quantities the amount of tannic acid in them is not dangerous, and the elaborate leaching process used in northwest California, where the acorn is a basic food, is not necessary."

Our recently excavated over 100 acorn leaching pits from the Sunken Village wet archaeological site, Sauvie Island, Portland, Oregon is the largest acorn pit leaching archaeological site anywhere along the entire West Coast of North America (including Oregon/California), this wet site certainly reflects the importance of this food

on the Central Northwest Coast of North America.

Once we became thoroughly introduced to acorn remains at the Sunken Village wet site, we then began to recognize their importance at the south Puget Sound Qwu?gwes wet site (45TN240) that the same crews had been excavating for five summer seasons. This was a true case of “You don’t see the thing because you don’t know how to look”. After two seasons at Sunken Village we knew ‘how to look’, and realized the importance of acorn remains as a source of carbohydrates at the Qwu?gwes wet site. Prior to this we saw them, but considered them

Douglas fir cone scales, a common macroflora in the site. No doubt this not seeing them possibly has happened at all excavated wet sites along the Northwest Coast, especially in the Central Coast. In this presentation I argue that salal and acorn ecofacts from the Central Northwest Coast represent substantial resources in the diets of this region.